Deciphering Browser Hieroglyphics: FileSystem (Part 3)

Part 3 in the Deciphering Browser Hieroglyphics series examines LevelDB databases and Chrome's FileSystem.

I spoke about "Deciphering Browser Hieroglyphics" at the SANS DFIR Summit 2017 in Austin, TX. A recording of most of the talk is available YouTube. I've translated the talk into written form for those who prefer to read (or skim) rather than listen. I've broken it up into parts:

Part 1: Introduction to Chromotopia

Part 2: LocalStorage & CyberChef

Part 3: LevelDB and Chrome's FileSystem

Part 3: LevelDB and Chrome's FileSystem

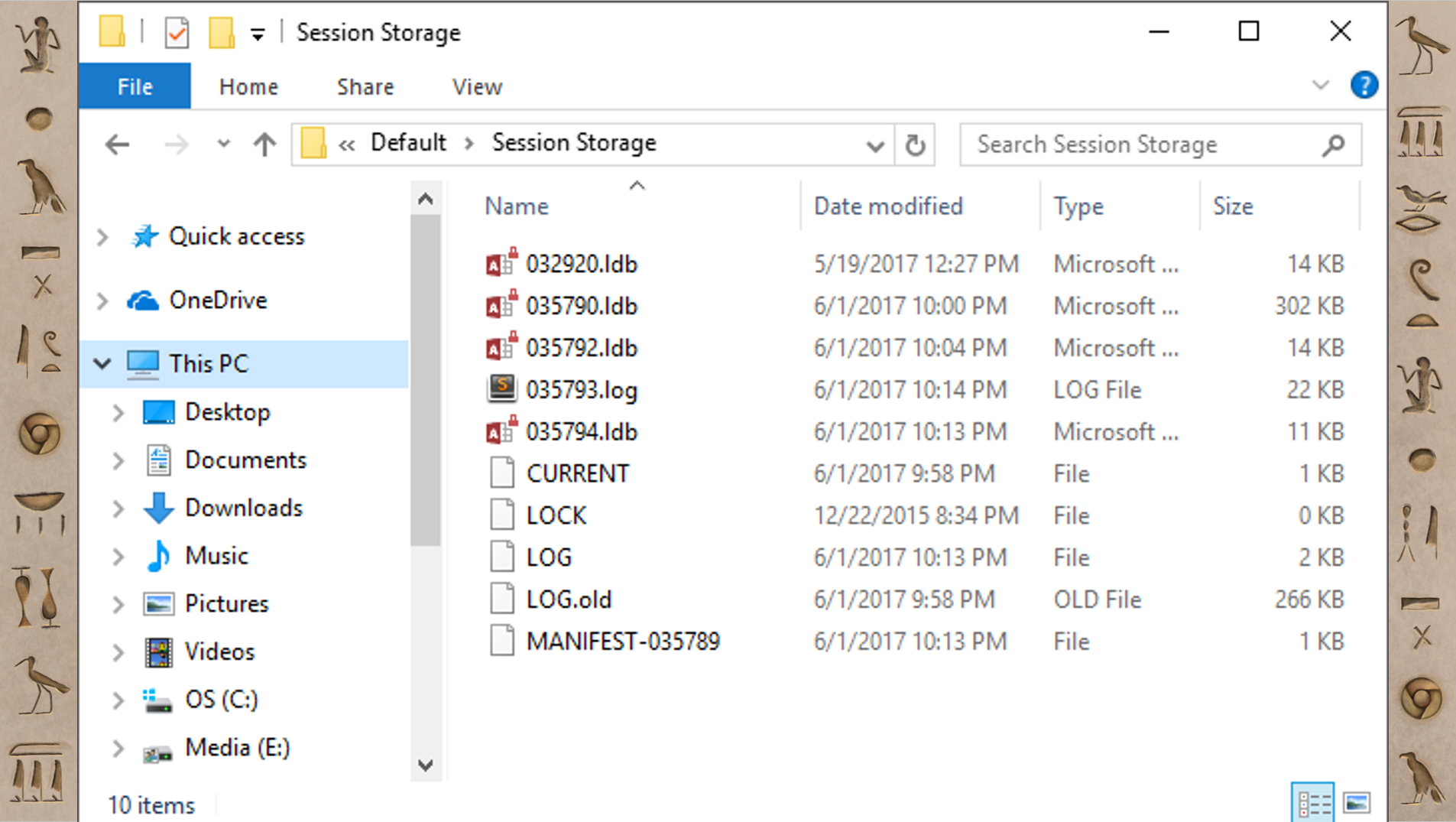

Now that we finished our first deciphering, we're going to head over to a more unexplored region. From our little quick survey we could tell that there's a lot of similarities in artifact structure, but we don't really know what they are exactly. Let's open up one of them and see like what it looks like. This happens to be the Session Storage folder and there are a bunch of files in there; some with .ldb or .sst extensions, LOCK and LOG, and some others.

If you open up those .ldb files, there's some stuff that looks like human-readable text, but it's kind of mangled and hard to actually make sense of. Now this structure (.ldb, .sst, etc) is repeated in a bunch of these kind of artifacts. I hadn't seen this before and I didn't know what it was. But, I'm lucky, because unlike the Europeans from a few hundred years ago, I just Googled it. What’s also helpful is because this is part of Chrome and Chromium, much of it is open source so I can go look at the source code. Eventually, I figured out that this is something called LevelDB.

LevelDB is a fast key-value storage library written at Google that provides an ordered mapping from string keys to string values. So basically, it does a limited number of operations (get/put/delete and so on) but it does it really fast. It has less features than SQLite, but it's way faster. Basically, Google designed and built it for their exact purpose. It has built in compression using Snappy (which is also made by Google) and Snappy’s main criteria is to be fast; you know... “snappy”. So that's why some of the stuff we could see was mangled but we could still read it; Snappy’s not very good at compression, but it's a very very fast compression. Now that we know that we're dealing with LevelDB, let's let's take a look at some of these artifacts.

FileSystem

The first one we're going to check out is the FileSystem. The FileSystem is similar to LocalStorage in that it is another HTML5 way of storing information. LocalStorage is a key-value pairs; FileSystem is like a virtual file system. If the website wants to store things with full files and folders and in a hierarchical structure, it can use the FileSystem. Let's just jump into the "File System" folder.

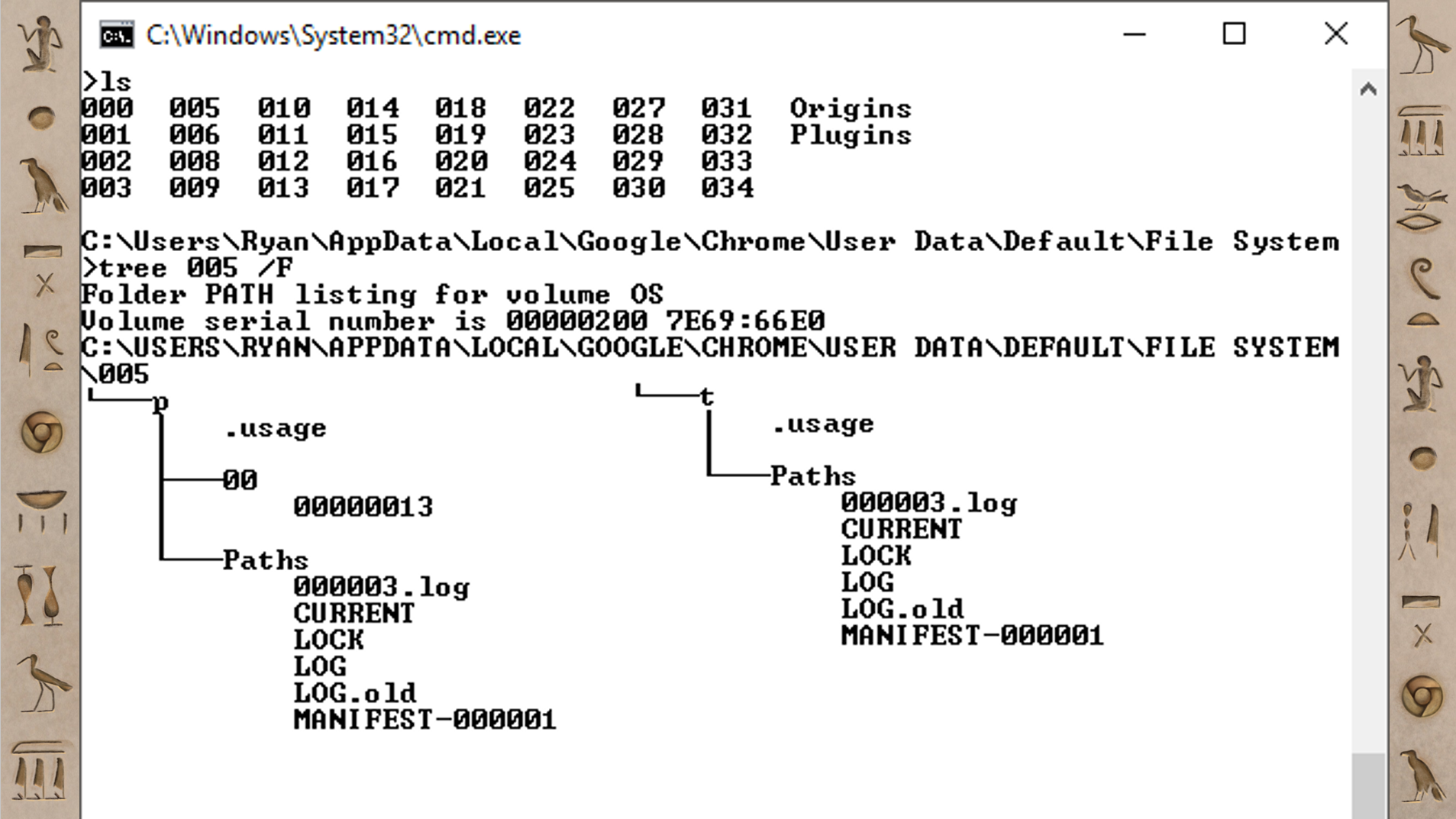

At the very top there's an ls command and the contents of that folder: a bunch of subdirectories that are named 000 - 034 (in this case there are 35 of these); then there's an Origins folder and a Plugins folder. The next step is to take a look inside one of those folders.

In 005, there's a p folder and a t folder; those stand for persistent and temporary. So there's two versions of this FileSystem - one that's temporary and one that’s supposed to hang around a bit longer, but they both have the same kind of structure. Inside the persistent one, there's another folder 00, and inside that there's just a file with an 8 digit integer: 00000013.

If you were to run the file command on that 00000013 file or open it in a hex viewer, you’d find it’s just a normal file. Similar to how you would find an “external” file in the Chrome Cache, this file is a text file or an image or whatever the site happens to want to store there.

However, in that Paths folder, there are a bunch of other types of files. There's a LOG file, a LOCK file; this looks like a LevelDB. If you open up that LevelDB, it has the information on how to translate the “File System” with the folders and the structure that the website sees, to the 00/00000013 we see on disk. It's how you map those two different things back and forth.

If you look in the Origins folder, at the very top that also has a LevelDB in it that maps these numbered directories, 000 through 034, to the website origins. The origins are named similarly to how the databases were named in the LocalStorage; something like https_www.pinterest.com_0. That’s the layout where we can find all the different raw files that are stored in the FileSystem.

FileSystem Example: Mega

But ok, that's cool, but what uses this and why do we care? Has anybody used or heard of Mega? It comes up in investigations every once in a while and it has a reputation for file sharing of some not-so-good things. But there are perfectly legitimate uses for it. I know a lot of forensic people share disk images or challenges on there because you get 50GB for free.

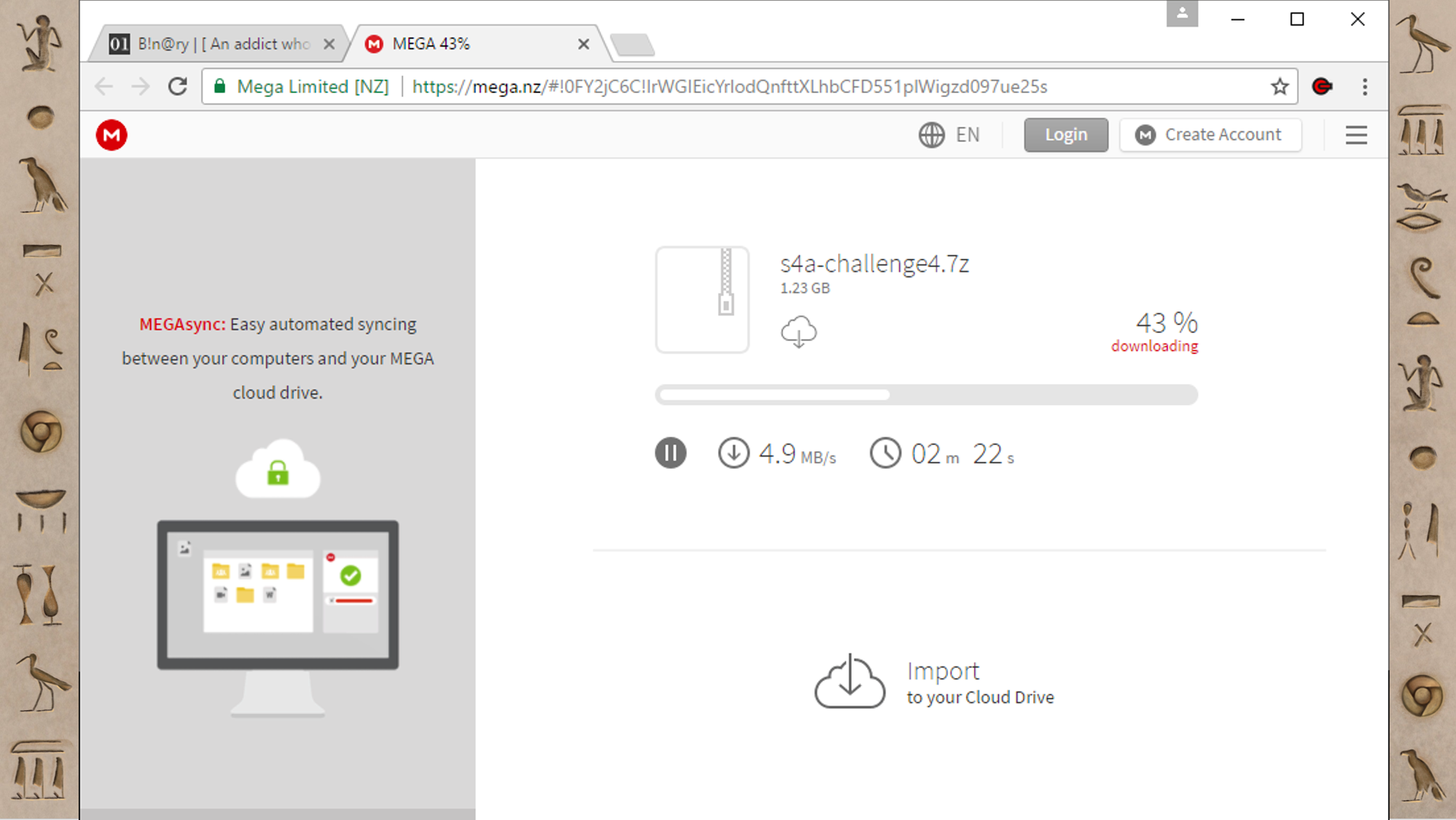

This is me downloading one of those challenges. The way Mega works when you download things is very different. When you are downloading something, it shows up in this progress bar inside the website, and then when it finishes there's the normal Chrome download popup at the bottom. But that “normal” Chrome download will finish really, really, fast; way faster than it could actually be downloading. So what Mega is doing is downloading the file into the Chrome FileSystem and then after that finishes, it's doing a local copy from the FileSystem to your Downloads folder. That's why the second one is super quick. Mega is not that good about cleaning up after itself. I have found files have been downloaded in Mega’s Chrome FileSystem area months after they were downloaded, even though the final downloaded file had been deleted or modified. It's a very interesting place to find files.

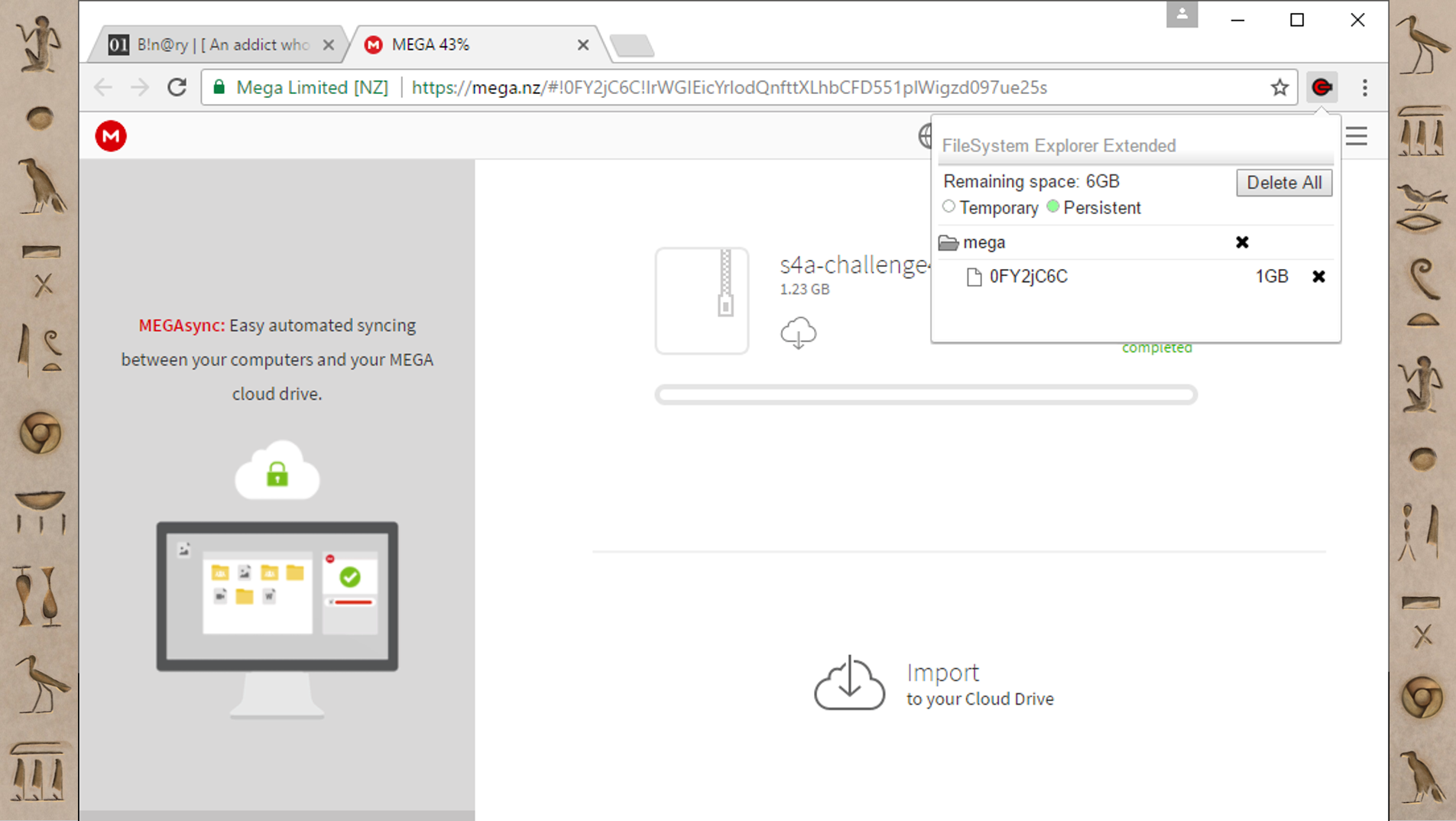

Unfortunately, the FileSystem is one of the few things in Chrome that you can't look at or inspect with the developer tools. However, someone has built an extension called FileSystem Explorer Extended that you can use to browse the FileSystem.

So with Mega, you can see there's just one folder (called mega) and there's this eight character named file (that happens to correlate to the URL if you look closely). Mega’s file structure is simple, but you can have big complicated file structures too.

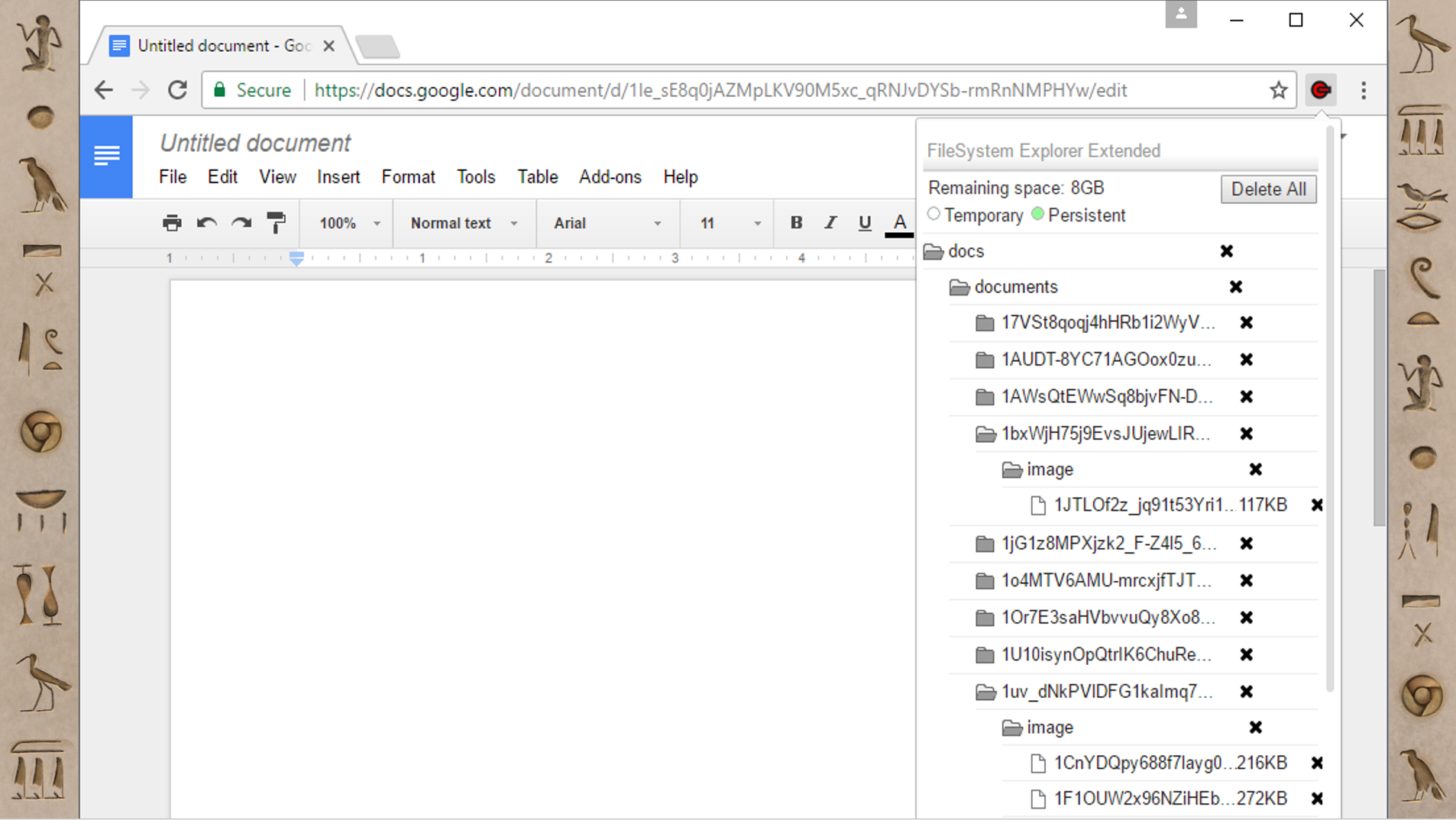

FileSystem Example: Google Docs

This is Google Docs, which also uses the FileSystem; it's not super surprising that Google products make heavy use of the advanced features of other Google products. I’ve found tons and tons of files in Google Docs’ FileSystem. In my experience they have mostly been images and fonts. If images are key in your investigation, I’ve found things that are that pretty dated in here, so it might be an interesting place to look.

FileSystem Parsing with Hindsight

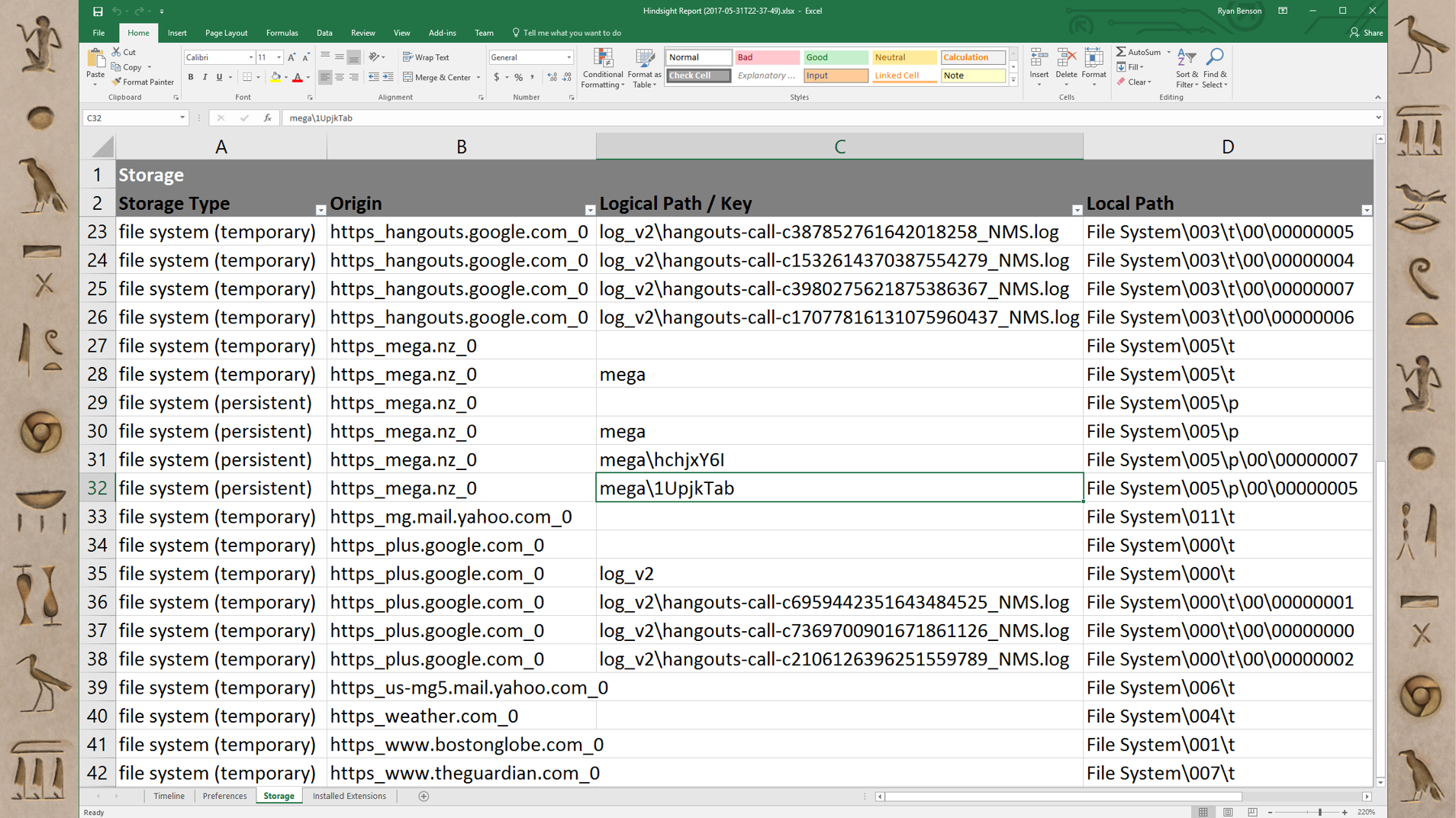

When you're deciphering things, you don’t always have to do it manually. If something is pretty straightforward to decipher, you might just want a tool to do that part for you so you can spend more of your analysis cycles figuring out how that fits into your larger investigation. I have an open-source forensics tool called Hindsight and I’ve built the ability to parse these FileSystem artifacts into it. If you’ve ever used Hindsight before, the most common way to view the output is in Excel.

The first tab is Timeline, but I've added a new tab for Storage, because these FileSystem items don't really fit well into a timeline. The first column is the type: whether it’s persistent or temporary. The second column is the web origin. The third column is the logical path that the website would have seen; it's the “folder structure”. The last column is the path to where to find that file in the user’s Chrome profile, if you want to grab it. It's pretty straightforward, but it's just doing a little bit of translating for you.

That's it for this section; up next is a look at Chrome's IndexedDB and Jupyter!